Around 40 volunteers with a conservative group questioning the integrity of Texas election results, as well as that of some election administrators, have begun a review of thousands of ballots from Tarrant County’s March 2020 GOP primary election.

Volunteers with the group, the Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity, told Votebeat Friday that their goal is to ensure the results of the election were accurate. Members are specifically counting votes in the Republican primary for U.S. Senate, in which Sen. John Cornyn won with 73% of the vote in Tarrant County over his closest challenger, who won 13% of the county’s votes. The group also alleges a range of fraudulent activities related to the 2020 November general election in Tarrant and other counties across the state but has offered no evidence to support the allegations.

“We’re not here as Republicans or Democrats,” said John Raymond, a volunteer with the group. “A lot of people don’t have faith in our elections, so we’re just here counting, making sure that what the secretary of state’s numbers say are right.”

“There’s nothing wrong with the election,” Tarrant County Election Administrator Heider Garcia said. “But the ballots are now public and it’s their right [to inspect them], and we will do everything that we have to do to make sure they can exercise their right to inspect public records.”

The group’s tallying of ballots — spurred by unsupported claims of voter fraud and of flawed election audits in Texas — began more than a week ago. In contrast with high-profile reviews of ballots elsewhere in the country, such as the 2021 review ordered in Maricopa County by the Arizona state Senate, the Tarrant ballot inspection has until now attracted almost no notice. In fact, even the secretary of state’s office said it had previously been unaware of Citizens for Election Integrity’s ballot review. But it’s unlikely to be the last such effort.

Volunteers have arrived daily at the Tarrant County election administration office’s ballot board room, which is where absentee ballots are typically counted.

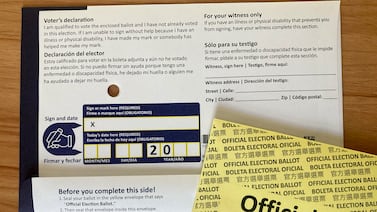

The group members inspecting ballots work in shifts — a morning shift from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and afternoon from 12:30 to 4:30 p.m. — as they progress through more than 300 boxes collectively holding more than 300,000 ballots. On Friday morning, about 15 volunteers sat in pairs at tables and flipped through all the ballots, one box at a time. Some volunteers compared the information on the ballots to data on their laptops. Some members of the group were also seen holding up the ballots up against the light. It’s unclear what they were looking for.

The tallying of the ballots will likely continue in this way for the next two weeks, Raymond said.

Charles Wedemeyer, another volunteer for the group, said he believes there’s a lot of unnecessary secrecy in the county’s elections.

“The act of voting is secret, but that’s it. The rest of it is public,” Wedemeyer said. “The citizens own this deal. But we had to wait 22 months to do this. It’s important for the records to be secure and protected but it’s not secret. The ballots should be available within five days.”

On Friday, upon seeing a photographer beginning to take photos for this article, the volunteers stopped what they were doing and walked out of the room.

Garcia, who’s led the office since 2018, said this is the first time he’s received a request of this scope: a large group of people seeking to physically review thousands of paper ballots.

But making that happen required massive time and resources from his office, which must keep staff members in the room with the ballots at all times.

“A lot of people in this office have had to learn to shuffle priorities,” Garcia said. The office’s elections staff includes the administrator, the assistant administrator, the voter registration manager, the elections manager and the operations manager. “We’re monitoring this process, we’re helping them, we’re answering questions, calls, and everything they need. But our people are also trying to register voters and we’re also trying to fulfill other information requests we have.”

The group first asked to inspect the March 2020 primary ballots last fall. But the Texas Election Code requires voted ballots to be retained in their original ballot box for 60 days after Election Day. On the 61st day, the “election custodian” may transfer those voted ballots to another secure container, where they must be kept for a 22-month preservation period. Anyone who wants to inspect the voted ballots must wait until after the 22 months, when they become subject to public records requests.

With the request pending and the clock ticking, the Tarrant County elections office had to set a plan, a policy, and procedures to have such a large group of people in the office for days on end while simultaneously ensuring the ballots’ security and continuing other work, Garcia said.

He drafted a policy for inspecting sensitive documents in person earlier this month.

It prohibits writing or marking instruments. All interaction with the documents by non-elections personnel is subject to video and in-person monitoring. Electronic devices with ethernet ports are not allowed in the inspection area; laptops, tablets, cellphones, and other electronic devices that do not have ethernet ports may be brought into the inspection area; among other guidelines.

A Tarrant County elections administration worker must be present in the room with the group at all times to answer any questions and to monitor the review of the documents.

Raymond said the group could next review ballots from elections in July 2020 and November 2020. Garcia said his office has already received requests to review the November 2020 election.Those ballots will become public record in September.

“This is just to start, it’s like a sample for us,” Raymond, who told Votebeat he is a retired military logistics officer, said. “We have to start somewhere and I’m guessing, these were also the ballots that were available first.”

Sam Taylor, assistant secretary of state for communications said election offices around the state are receiving large numbers of public information requests, and they are likely not going away any time soon.

“I think for most counties it’s in their interest to be as transparent as possible with their voters,” Taylor said. “Now closer to November, [county election administrators] are probably not going to be able to set aside entire rooms for this kind of stuff. It will take extra resources.”

Not every state considers voted ballots to be public records. In an email to Votebeat, Saige Draeger, an elections and redistricting policy associate with the National Conference of State Legislatures, said some states distinguish between physical ballots and images of ballots, treating them differently under the law, and many states are silent on the question entirely. Other states that specify that physical ballots are public records include Colorado and Florida, provided that the ballots contain no information that could be used to identify voters, Draeger said.

Voting rights advocates in Texas and elsewhere have sounded the alarm over the activities of conservative election integrity groups.

“It’s really ominous for what we may see if this election and then in 2024,” said James Slattery, senior attorney for the Texas Civil Rights Project’s voting rights program. “Our democracy really relies on people having faith that they are casting a ballot that counts and that our leaders are elected through an accurate count of those votes. So efforts like these, even when they can’t substantiate their allegations of fraud, contribute to a growing impression that elections are rigged somehow, and that elected leaders are fraudulently in office and over the long term, that kind of undermining of faith in democracy will be fatal to our system.”

Anthony Gutierrez, executive director of Common Cause Texas, a government watchdog group, said a ballot review such as the one in Tarrant County “elevates the narrative that election administrators are somehow not doing their jobs properly or even worse trying to sway elections.”

“It’s a really dangerous lie that is being sold to a lot of people and frankly, it’s putting election administrators in a lot of danger,” Gutierrez said. “It all stems from this lie of elections about our elections not being safe.”

Mei Wang, a volunteer with the Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity, told Votebeat Friday the group isn’t trying to keep anyone away from the polls.

“We want people to vote, we need people to come vote, and we can audit,” said Wang, who told Votebeat she has an accounting and auditing background. “We want audits to be done more regularly, quarterly, and we want to correct this problem.”

In Texas all counties are required to audit their results by doing a partial manual count for every election, in 1% of precincts or three precincts. Tarrant County did a manual count in 2020 as part of its audit for the Senate race the group is inspecting, Garcia said.

Natalia Contreras is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org. If you know of someone using public-records law to inspect voted ballots, please contact us.